Further to my reflections on American TV shows over the last few days, someone pointed out that there is not much of a commentary included. I added a few thoughts to the end of the second post, but clearly that was not enough. So I thought I’d try to expand on that.

What effect did these shows have on me as an individual, and my generation?

This is going to be problematic. I can certainly try to explore the effect that they had on me, but beyond that it will have to be conjecture at best.

Firstly then, what is the nature of a hero? Traditionally, a hero was semi-divine, featuring in the mythology of ancient Greece. They were superhuman in some way, admired for their courage or other noble qualities, and often engaged in a feat of self-sacrifice. This definition has been modernised somewhat, taking into account literary heroes, which are simply (and slightly erroneously) seen as the main protagonist of a work of fiction, someone who is generally associated with positive qualities. Often a modern hero will be an everyman, an ordinary person in an extraordinary situation who rises to the challenge facing them. In the real world, of course, a hero is just someone who is respected for some kind of achievement, often showing bravery by risking their own life, but we aren’t interested in real life here!

Heroes are central to our emotional landscapes, meaning that we need heroes (either real or imaginary) in order to give us something to aspire to. They have the touch of perfection, but almost inevitably with enough of a flaw to be attainable by mere mortals. At least, that’s how it seems. Most of us are actually far too real, too normal, too boring, to ever achieve heroic status, however hard we may try. Besides, most of us look ridiculous in spandex. But we have invented heros ever since we started thinking, almost. The ancient Greeks had heroes, the Egyptians, the Scandinavians, the Celts. We have always needed someone with the physical and mental strength to stand up for the little people, to face down the tyrant, to win the day.

An action show, or movie, needs a hero (or possibly an antihero, but more of them in a bit), as well as a foil for them, a villain of some sort. This could be, in the case of some of the TV shows discussed before, a villain of the week, a one-off bad guy who is defeated before the hero moves on. Or it could be a recurring bad guy, or succession of essentially identical bad guys working for one uber-villain. Battlestar Galactica is a perfect example of the latter, with the Cylons repeatedly throwing themselves at the fleet, following the orders of the Imperious Leader, while an example of the former would be Knight Rider, where Michael Knight would drive around looking for desperate people that he could help. The A-Team, of course, would fall somewhere between the two, as they would often be fighting a villain of the week while simultaneously trying to avoid capture by the military police led by Colonel Decker. Heroes need someone to fight who represents the bad in the world. This could be repressive authority, the ‘tyranny of evil men’, corporate greed. It needs to be something that affects ordinary people, people who, for whatever reason, are powerless against it.

80s heroes embraced the anti-authority angle with gusto. The A-Team, The Dukes of Hazzard and Airwolf all feature heroes who work against the accepted face of government in some way, although all are sympathetic characters. Hannibal and co. are wrongly convicted of a crime, the Duke boys are charming rogues guilty of nothing more than a little illicit booze smuggling and Stringfellow Hawke was being blackmailed to work for a distinctly dubious and secretive arm of government. The audience is firmly on the side of the rebel, especially in America, where the rebel is part of their national history. The American nation was born out of rebellion (specifically rebellion against the British – just watch any Mel Gibson film of the last fifteen years), so it is fitting that their heroes should now take on that role. Quite often, various branches of Federal government are used as the villain, be it the CIA, the FBI, local law enforcement or whatever. This shows us that although Americans are fiercely proud of their rebellious beginnings, they do not necessarily trust the systems put in place for the protection of their nation. This was especially odd in the 80s, when America was deep in the Cold War, following a strong anti-communist policy. The idea of heroes going around helping people who were unable to help themselves was a deeply communistic one, totally at odds with the capitalist American dream. And yet these heroes flourished.

The rebel is iconic, it runs through folklore and history. American history in particular is full of these men – and they are almost exclusively men: Patrick Henry; George Washington; Sam Houston. This carries through into television and film: Han Solo; Jim Stark; Tyler Durden. The 80s were more open to the idea of the rebel in television than earlier decades, partly because of the oppressive political climate, partly because of the decreasing cost of producing television shows combined with larger budgets, which made it easier to churn out action and science-fiction shows with reasonable (if not excellent) production values. Glen Larson and Stephen Cannell, among others, were used to capitalize on this situation with their huge outpouring of shows. But these shows were made by men, starred men and dealt with male relationships. The female roles were generally little more than eye candy, without any depth or importance to the plot, mostly there just to be kissed by the heroes and occasionally get kidnapped. The A-Team in particular was criticised for being sexist, and indeed some of the stars were openly hostile to the idea of including regular female cast members. It’s true that very few action shows from that period had female leads: in the late 70s, Wonder Woman, as portrayed by Lynda Carter, had pranced across the small screen in her satin tights, Lindsay Wagner was playing The Bionic Woman at around the same time, and the classic Charlie’s Angels kept karate kicking for a year or two longer. But as the 80s dawned, these shows disappeared, leaving women to fill the fluff roles, supporting the more traditionally ‘heroic’ men.

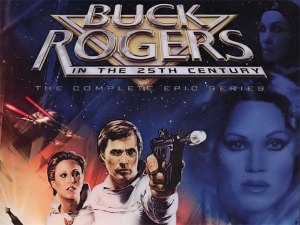

The depiction of violence is another area where these shows stand out. Famously, The A-Team never killed anyone, despite spraying bullets and explosives around like champagne on the winner’s podium. Michael Knight rarely (if ever) fired a gun, but did manage to run half a dozen cars off the road in every 45 minute episode (this may be an exaggeration). Airwolf launched missiles and rockets with wild abandon, Blue Thunder‘s cannon almost never stopped firing and even the Duke boys forced Hazzard County to spend the GDP of a medium-sized South American country on replacement police cars. And yet no-one ever died. No blood was ever spilt. The reason for this was obvious, of course: prime time television couldn’t allow it. The exceptions to this rule were Battlestar Galactica and Buck Rogers in the 25th Century, as they were only shooting aliens and robots, which was somehow more acceptable to the censor’s sensibilities. This violence, harmless as it may appear to a generation dulled by Quentin Tarantino and the Coen brothers, was problematic at the time. Networks worried that even this level of ‘cartoon’ violence would be disliked by parents, although relatively few complaints were received. It has been suggested that the over-the-top violence was the cause of the demise of these shows, as viewers eventually preferred less ‘masculine’ shows, turning instead to more family themed programming.

The 80s action style lived on for a few more years in the cinema, evolving eventually into the antihero movies of Leon and The Boondock Saints, characters who will do whatever it takes to do the right thing, even if that means shooting a whole bunch of people in the face. No A-Team style cartoon violence there, although the motives (help people who cannot help themselves) remain the same. The targets changed too, becoming more focused on organised crime rather than corrupt government or local criminals. Today, of course, we have a range of villains to shoot at. Our post-modern take on the action movie means that we can’t throw a brick into a crowd without hitting someone that we can call a villain: lawyers, capitalists, terrorists, gangers, activists, bent coppers, the list is virtually endless. But the reasons, and the rebellious nature of our heroes, remains. How many cop shows or movies haven’t featured a cop arguing with his or her superiors about the best way to deal with a criminal? How many shootouts don’t involve hundreds of bullets missing their targets? How many car chases don’t involve one of the chasing cars crashing into civilian traffic at an intersection? These shows have helped to shape the collective unconsciousness. We now expect to see these conventions acted out, even if we dismiss them as clichéd, and feel somehow cheated when they are ignored.

The sexism angle is still with us. Strong female characters are more accepted, but still not common, and the argument remains that most of them are simply masculinised, rather than being strong in their own right. Linda Hamilton in Terminator 2: Judgement Day has lost the femininity and innocence of the first film and bulked up, becoming muscular, dressing in baggy, form-hiding combat trousers, and failing to be the mother-figure that young John Connor needs. Milla Jovovich in the Resident Evil series is a combat expert with some superhuman abilities, turning her into nothing more than a robotic killing machine. Some films are more effective, namely Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon and House of Flying Daggers, which attempt to show women operating in a masculine society without losing their femininity. Crouching Tiger… presents the character of Yu Shu Lien as submissive to the masculine society but still able to operate as a warrior, maintaining both her masculine role and her feminine one.

But did the 80s shows change us? Did they make us see the world in a certain way? Judging by the recent run of 80s series being rebooted or made into Hollywood movies, I’d venture to suggest that they have made a lasting impression on my generation: The A-Team, The Dukes of Hazzard, Miami Vice, Charlie’s Angels, G.I. Joe, Battlestar Galactica. The rebel-as-hero archetype is still with us, as is the antihero, although both predate the 80s by hundreds of years, it was that decade that saw them truly come into their own. Heroes are not infallible, and we don’t want them to be. Superman is the least interesting of the mainstream superheroes, largely because he is too close to perfection. There is no way for us to relate to him. In the recent reboot of that franchise, the film-makers had to give him both a son (to give his enemies a new way to hurt him) and a literal mountain of Kryptonite! Batman, on the other hand, is really quite damaged and flawed. He is much darker and the audience likes him for it, recognising some of their own flaws behind that mask.

The 80s heroes were more innocent in many ways, hovering on the fringes of criminality without ever venturing in too deep. That would have been too disturbing for the young audience. Somewhere along the line, we lost that innocence. As a result, TV heroes have lost a lot of their power to thrill and excite us.

I think that’s a bad thing. What do you think?